Colonized Sexuality

Colonized sexuality is the body crossed by norms that do not belong to it. Imposed by Christian, patriarchal, and Eurocentric epistemologies, it turns desire into discipline, skin into a border, gender into a prison. To colonize sexuality is to sever pleasure from spirit, affection from territory, the body from history. It is to erase entire cosmologies where sex was ritual, connection, passage, and vital force. To decolonize sexuality, then, is not only an act of resistance

Colonized sexuality is not merely the repression of individual desire — it is the systemic rearrangement of entire erotic, affective, and relational cosmologies through the violent imposition of Western, patriarchal, and Christian norms. As Aníbal Quijano defines in his theory of coloniality of power, colonization was not only a territorial project, but also an epistemic and ontological one. Sexuality was a key target of this transformation — a space where bodies were classified, desires were regulated, and forms of life were subjugated to fit within a Eurocentric model of intelligibility.

Maria Lugones expands this idea by introducing the concept of the coloniality of gender, revealing how colonialism did not just impose hierarchies of race and class, but also forcibly introduced a binary gender system and heteronormative matrix where diverse pre-colonial gender expressions and sexualities were erased or demonized. In many Indigenous, Afro-diasporic, and ancestral worldviews, sexuality was not reduced to reproductive function or moral control, but existed as a force of connection, ritual, community, and spirituality. The colonial project severed this sacred link between body and territory, between sex and meaning.

Gloria Anzaldúa, in her writings on the borderlands, reminds us that colonized sexuality also emerges as a site of internal fracture — a space where hybrid identities (queer, mestiza, racialized) are forced to navigate shame, fragmentation, and invisibility within both dominant culture and their own communities. Her work affirms that to reclaim sexuality is also to reconfigure language, myth, and flesh — a border practice that is both spiritual and political.

Achille Mbembe points out that the colonial order functions through necropolitics — the regulation of who may live and who must die. Within this framework, the sexuality of Black, queer, Indigenous and trans bodies becomes a field of state control, medicalization, and hypervisibility paired with disposability. The erotic life of the colonized subject is policed, exoticized, or erased — never autonomous.

Ochy Curiel, building from Afro-Caribbean feminism, reminds us that decolonizing sexuality cannot be a mere liberal inclusion of "diverse" sexualities into the colonial order. Rather, it requires a rupture with the racial-capitalist and patriarchal logic that continues to shape intimacy, desire, kinship, and relationality. It requires unlearning the colonial gaze and recovering ways of being together that do not rely on domination or commodification.

To decolonize sexuality, then, is not just to resist — it is to reimagine. It is to reactivate ancestral memories where sexuality was sacred, creative, and communal. It is to honor pleasure not as a luxury, but as a political and spiritual right. And above all, it is to reclaim the body as a site of knowledge, healing, and transformation — no longer a border to be patrolled, but a territory to be loved.

Pudor

Pai, afasta de mim esse cálice

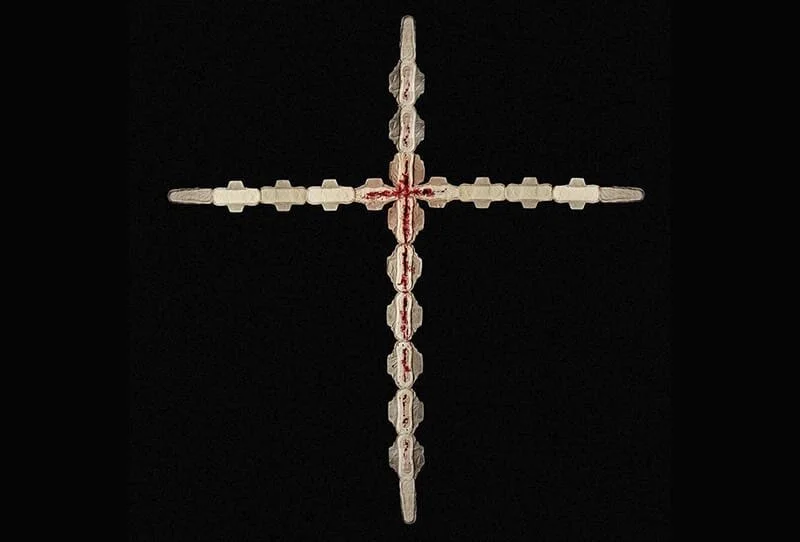

For this performance, I counted at least 10 men and the act would be me in the crucifixion position, but without the cross, because it brings us back to the masculine figure and I wanted the female figure to be the center of the action. In this action, I am the mirror and I am willing to suffer this humiliation and I make it possible and a group of men in line must urinate on my feet, one at a time.

My first analysis was that for the sake of this feasibility of wanting to suffer this "supposed" humiliation and face a concept of subalternity while placing this sign mirroring the other, thus exalting a pulse and a "negative" attitude that many deny having and, having as a backdrop, the outline of a male figure, however, a woman's body, naked, in order to deface and deconstruct signs assigned to me, culturally by them.

I've been trying to carry out this performance about a year and during the first attempt when I was undressing, I was blocked by the police, so, during the second time I decided to approach people and perform the act in an abandoned school in Cambuci - SP. I approached several people and initially my priorities were: artists, actors from liberal or LGBT theaters, people involved with fetish and sex professionals. During the entire process, about 80 people were approached, but many of these people did not answer me, a few stopped speaking to me and others blocked me from social networks.

I Miss You

The devastation of the feminine begins in its vital energy, in search of "power" and it is these relations of power and of absence, that women who have already left, struggling, do, is what this performance speaks about. A circle of fire recalls pagan rituals, but also the burning of women during the Inquisition. Nature, vital energy, ablaze, a female body amidst the circle of fire, wearing social clothing and a sash and crown of Miss, "the place of acceptance of the feminine, not the place where I wanted to be." The saying; "I MISS YOU" and the position in which gods pose in their paintings, figurines, symbols, and in the hand, a vagina-like sore.

Like the 9 phases of the moon, but this time, on fire as the sun, burns 9 sheets of paper written front-of-verse with names of women victims of feminicide in various languages, as a nature that connects and inspires change and evolution; I miss you, we miss you.

To Curate your Self

Curatorship, in the context of art, is an investigative exercise whose purpose is to communicate something to someone through the selection of objects — a process that involves deciding what will or will not be shown. Traditionally, the curator is seen as a specialist who operates from a vertical perspective, acting as an authority on a specific subject. However, contemporary art has shifted this paradigm by embracing authorship from the public itself, recognizing that it is the audience who now performs their own act of curation — connecting to their personal histories through the visibility of the exhibition.

At its foundation, this project incorporated performative gestures designed to encourage public participation, inviting individuals to experience a symbolic-artistic catharsis of their own memories. These acts offered a space to confront and release haunting past events, transforming them into a shared aesthetic process.

This work continues my earlier project developed at MAC Bogotá on decolonization and sexuality. The initial experiments were rooted in my personal history and later adapted to be applied to others. The ultimate goal was to create a method of reprocessing that is accessible, collective, and emotionally resonant.